How Victorian Saloon Owners Created Modern Behavioral Economics

The Economics of Desperation in 1875 New Orleans

The year is 1875. You’re a working-class man in New Orleans, earning barely enough to survive. Your stomach growls as you pass a gleaming saloon where an incredible aroma wafts from the doorway. Inside, you spot something that seems too good to be true – tables laden with “immense dishes of butter,” “large baskets of bread,” “a monster silver boiler filled with a most excellent oyster soup,” and “a round of beef that must have weighed at least forty pounds.”

The catch? You need to buy a 15-cent drink to access this feast.

The math seems impossible. That same meal would cost you a full dollar at an other restaurant – nearly 7 times the price of the drink. Yet saloon after saloon across America was offering this deal, and somehow staying profitable. What were they thinking?

How the Strategy Actually Worked and Succeeded

The free lunch wasn’t really about the food. It was about time, psychology, and customer behavior. Everything about the strategy was designed to motivate customers to purchase multiple drinks.

Salt Peanuts: Every item was heavily salted – pretzels, cured meats, pickled vegetables, and salted fish. The theory behind all this, and it was a good theory, was that a couple of shot glasses or steins produced appetite — and the salty goodies, in turn, produced a mighty thirst.

Stay and Enjoy: A hungry worker might grab a quick 5-cent beer and leave. A worker enjoying a full meal would linger for multiple rounds, often spending 15-20 cents instead.

Social Pressure: The nearly indigent “free lunch fiend” was a recognized social type who tried to eat without buying drinks. But most customers felt social pressure to order drinks while eating in a drinking establishment.

The numbers prove the strategy worked. Free Lunch drove Foot Traffic

In Chicago with 3,000 to 3,500 saloons – as in other cities – saloons provided free lunch every day. Newspaper estimates showed that saloon keepers fed 60,000 people a day – acquiring customers who would normally patronize other establishments, such as religious, charitable and municipal, for food.

The Zero Price Effect

What those Victorian saloon owners couldn’t have known is that they had stumbled onto one of the most powerful principles in behavioral economics – what Duke University professor Dan Ariely calls the “Zero Price Effect.”

Ariely discovered that “free is an emotional hot button — a source of irrational excitement” that goes far beyond rational value calculation.

A compelling example of this comes from Amazon’s early free shipping experiment. When Amazon launched free shipping with the purchase of a second book, sales jumped dramatically in every country except France. Amazon’s team investigated, thinking perhaps the French were more rational. They discovered that France hadn’t actually offered free shipping – they had charged one franc (about 20 cents). From a pure economic standpoint, the two offers were nearly identical. But that tiny 20-cent charge was enough to eliminate the psychological power of “free.” When France switched to truly free shipping, sales immediately jumped to match other countries.

The Zero Price Effect is the phenomenon of shoppers tending to choose a free product more often than its inherent utility would suggest. When something is free, we don’t just see it as a good deal – we see it as risk-free, guilt-free, and irresistibly attractive. Irrationality may blind us to the downsides of the deal.

Ariely’s research revealed something even more powerful about the Victorian strategy. The free lunch wasn’t just exploiting the attraction to “free” – it moved the consumer’s thinking from what behavioral economists call “market norms” to “social norms.”

Here’s the difference: Payment for something – anything – is a transaction. When something is given freely, it’s akin to hospitality. The saloon customers didn’t feel like they were buying lunch – they felt like the generous hosts were taking care of them. This created emotional bonds that went far beyond a simple business transaction.

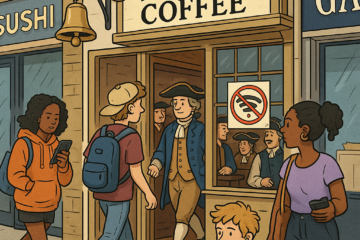

But here’s the crucial warning that Victorian saloon owners learned the hard way: once you switch from “free” to “paid,” you can’t easily go back. Ariely found that when businesses try to charge for something that was previously free, customers don’t just return to normal – they actually become less loyal than if they’d been charged from the beginning.

Imagine if your favorite coffee shop suddenly started charging for WiFi that had always been free. You wouldn’t just accept it – you’d feel betrayed. That sense of hospitality would be permanently broken.

The saloons that tried to start charging for their lunch (even small amounts) often found they lost more customers than the economics would predict. They had accidentally destroyed the social relationship they’d built with their regulars.

The Free Lunch Lives On

Today’s most successful restaurants are implementing these Victorian principles:

- Happy Hour Appetizers: Restaurants offer heavily discounted or free appetizers during slow periods, knowing customers will order full-priced drinks and often stay for dinner – exactly like the saloon model.

- Bread and Chips: “Complimentary” bread baskets and chips aren’t just courtesy – they’re psychological anchors that make the meal feel more generous and keep customers at the table longer.

- Restaurant/Coffee Shop WiFi: Starbucks offers free internet not as a public service, but because laptop users occupy tables for hours and purchase multiple items – the modern equivalent of salted pretzels keeping people drinking.

- Loyalty Programs: “Free” rewards create the same social norm relationships that saloons built, making customers feel valued rather than merely transacted with.

- Sampling Strategies: Costco’s weekend sampling stations cost millions annually but increase average basket size and store dwell time dramatically, proving the zero price effect still works.

The Timeless Truth

The phrase “there’s no such thing as a free lunch” originated from this very practice, as observers recognized that the “free” food was subsidized by drink sales. But perhaps that misses the point.

Victorian saloon owners didn’t just stumble onto an effective tactic – they were unknowingly applying sophisticated behavioral economics principles that wouldn’t be formally identified for another 130 years. As Ariely observed in Predictably Irrational, “Our irrational behaviors are neither random nor senseless—they are systematic and predictable”

The free lunch strategy succeeded because it aligned perfectly with these predictable irrationalities, and the free lunch is very much alive and thriving today. Its psychological blueprint drives billion-dollar businesses today, but perhaps is not used as effectively in the restaurant industry as it could be. Sometimes the best way to get paid is to give something away for free – a lesson those Victorian saloon owners learned through trial and error, and one that modern behavioral science has finally explained.

0 Comments